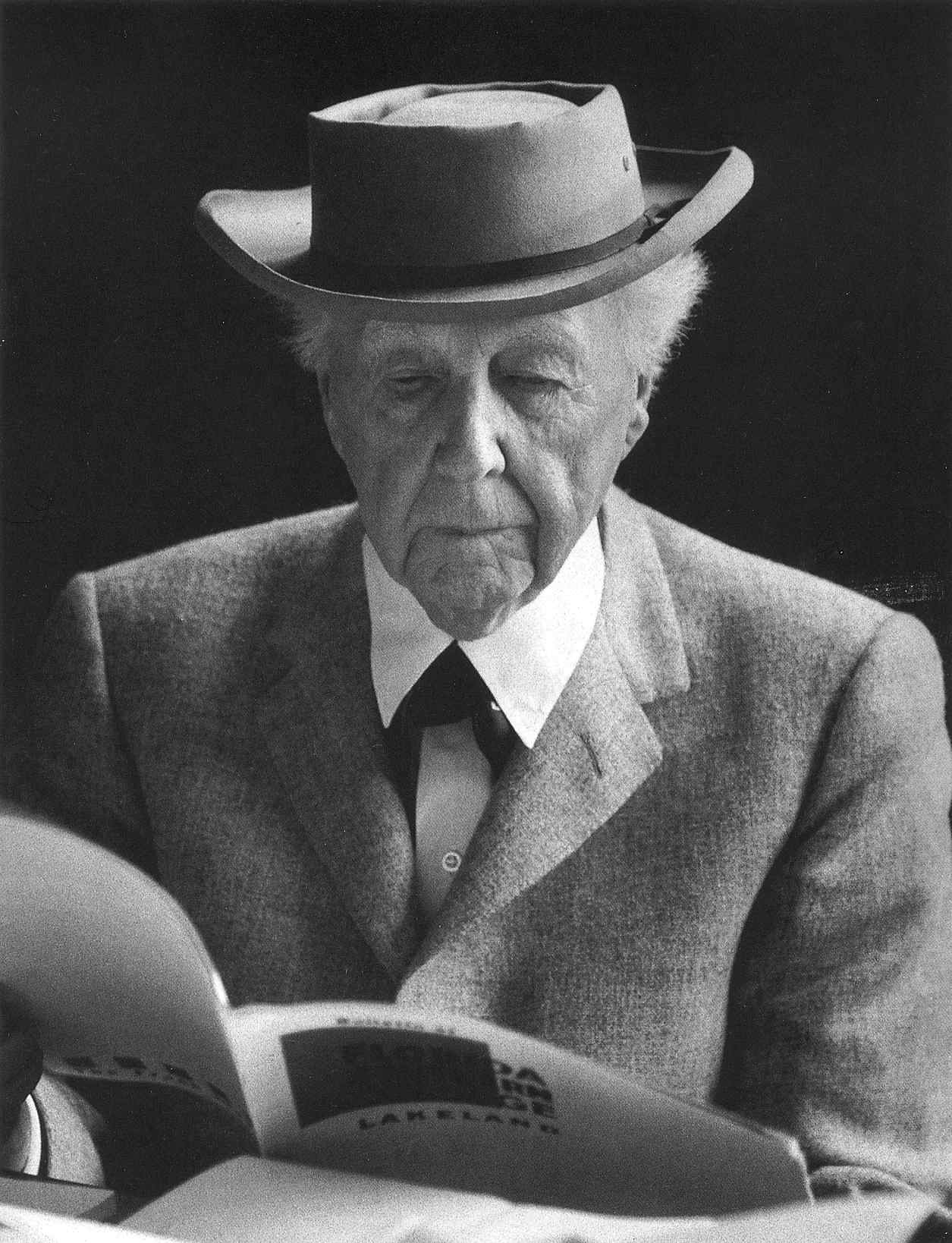

Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8, 1867, in Richland Center, Wisconsin. After college, he became chief assistant to architect Louis Sullivan. Wright then founded his own firm and developed a style known as the Prairie school, which strove for an “organic architecture” in designs for homes and commercial buildings. Over his career he created numerous iconic buildings. He died April 9, 1959.

Early Life

Frank Lloyd Wright was born June 8, 1867, in Richland Center, Wisconsin. (Although he often stated his birthday as June 8, 1869, records prove that he was in fact born in 1867.) His mother, Anna Lloyd Jones, was a teacher from a large Welsh family who had settled in Spring Green, Wisconsin, where Wright later built his famous home, Taliesin. His father, William Carey Wright, was a preacher and a musician. Wright’s family moved frequently during his early years, living in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Iowa before settling in Madison, Wisconsin, when Frank Lloyd Wright was 12 years old. He spent his summers with mother’s family in Spring Green. An outdoorsy child, Wright fell deeply in love with the Wisconsin landscape he explored as a boy. “The modeling of the hills, the weaving and fabric that clings to them, the look of it all in tender green or covered with snow or in full glow of summer that bursts into the glorious blaze of autumn,” he later reminisced. “I still feel myself as much a part of it as the trees and birds and bees are, and the red barns.”

In 1885, the year Wright graduated from public high school in Madison, his parents divorced and his father moved away, never to be heard from again. That year, Wright enrolled at the University of Wisconsin at Madison to study civil engineering; in order to pay his tuition and help support his family, he worked for the dean of the engineering department and assisted the acclaimed architect Joseph Silsbee with the construction of the Unity Chapel. The experience convinced Wright that he wanted to become an architect, and in 1887 he dropped out of school to go to work for Silsbee in Chicago.

Prairie School Architecture

A year later, Wright began an apprenticeship with the Chicago architectural firm of Adler and Sullivan, working directly under Louis Sullivan, the great American architect best known as “the father of skyscrapers.” Sullivan, who rejected ornate European styles in favor of a cleaner aesthetic summed up by his maxim “form follows function,” had a profound influence on Wright, who would eventually carry to completion Sullivan’s dream of defining a uniquely American style of architecture. Wright worked for Sullivan until 1893, when he breached their contract by accepting private commissions to design homes, and the two parted ways.

In 1889, a year after he began working for Louis Sullivan, the 22-year-old Wright married a 19-year-old woman named Catherine Tobin, and they eventually had six children together. Their home in the Oak Park suburb of Chicago, now known as the Frank Lloyd Wright home and studio, is considered his first architectural masterpiece.

It was there that Wright established his own architectural practice upon leaving Adler and Sullivan in 1893. That same year, he designed the Winslow House in River Forest, which with its horizontal emphasis and expansive, open interior spaces is the first example of Wright’s revolutionary style, later dubbed “organic architecture.”

Over the next several years, Wright designed a series of residences and public buildings that became known as the leading examples of the “Prairie School” of architecture. These were single-story homes with low, pitched roofs and long rows of casement windows, employing only locally available materials and wood that was always unstained and unpainted, emphasizing its natural beauty. Wright’s most celebrated “Prairie School” buildings include the Robie House in Chicago and the Unity Temple in Oak Park. While such works made Wright a celebrity and his work became the subject of much acclaim in Europe, he remained relatively unknown outside of architectural circles in the United States.

Taliesin Fellowship

In 1909, after 20 years of marriage, Wright suddenly abandoned his wife, children and practice and moved to Germany with a woman named Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a client. Working with the acclaimed publisher Ernst Wasmuth, while in Germany Wright put together two portfolios of his work that further raised his international profile as one of the leading living architects. In 1913, Wright and Cheney returned to the United States, and Wright designed them a home on the land of his maternal ancestors in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Named Taliesin, Welsh for “shining brow,” it was one of the most acclaimed works of his life. However, tragedy struck in 1914 when a deranged servant set fire to the house, burning it to the ground and killing Cheney and six others. Although Wright was devastated by the loss of his lover and home, he immediately began rebuilding Taliesin in order to, in his own words, “wipe the scar from the hill.”

The next year, in 1915, the Japanese Emperor commissioned Wright to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He spent the next seven years on the project, a beautiful and revolutionary building that Wright claimed was “earthquake proof.” Only one year after its completion, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 devastated the city and tested the architect’s claim. Wright’s Imperial Hotel was the city’s only large structure to survive the earthquake intact.

Returning to the United States, he married a sculptor named Miriam Noel in 1923; they stayed together for four years before divorcing in 1927. In 1925 another fire, this one caused by an electrical problem, destroyed Taliesin, forcing him to rebuild it once again. In 1928, Wright married his third wife, Olga (Olgivanna) Ivanovna Lazovich—who also went by the name Olga Lazovich Milanov, after her famous grandfather Marko.

With architectural commissions grinding to a halt in the early 1930s due to the Great Depression, Wright dedicated himself to writing and teaching. In 1932, he published An Autobiography and The Disappearing City, both of which have become cornerstones of architectural literature.

That same year he founded the Taliesin Fellowship, an immersive architectural school based out of his own home and studio. Five years later, he and his apprentices began work on “Taliesin West,” a residence and studio in Arizona that housed the Taliesin Fellowship during the winter months.

Fallingwater Residence

By the mid-1930s, approaching 70 years of age, Wright appeared to have peacefully retired to running his Taliesin Fellowship. Then, in 1935, he suddenly burst back onto the public stage to design many of the greatest buildings of his life. Wright announced his return to the profession in dramatic fashion in 1935 with Fallingwater, a residence for Pittsburgh’s acclaimed Kaufmann family. Shockingly original and astonishingly beautiful, Fallingwater is marked by a series of cantilevered balconies and terraces constructed atop a waterfall in rural southwestern Pennsylvania. It remains one of Wright’s most celebrated works, a national landmark that is widely considered one of the most beautiful homes ever built. Then in the late 1930s, Wright constructed about 60 middle-income homes known as “Usonian Houses.” The aesthetic precursor to the modern “ranch house,” these sparse yet elegant houses employed several revolutionary design features such as solar heating, natural cooling and “carports” for automobile storage.

During his later years, Wright also turned increasingly to designing public buildings in addition to private homes. He designed the famous SC Johnson Wax Administration Building that opened in Racine, Wisconsin, in 1939. In 1938, Wright put forth a stunning design for the Monona Terrace Civic Center overlooking Lake Monona in Madison, Wisconsin, but he failed to secure public funding for the project. In 1992, 33 years after the architect’s death, the state finally approved funding for the building’s construction, which was completed in 1997, nearly 60 years after Wright finished his designs.

In 1943, Wright began a project that consumed the last 16 years of his life—designing the Guggenheim Museum of modern and contemporary art in New York City. “For the first time art will be seen as if through an open window, and, of all places, in New York. It astounds me,” Wright said upon receiving the commission. An enormous white cylindrical building spiraling upward into a Plexiglass dome, the museum consists of a single gallery along a ramp that coils up from the ground floor. While Lloyd’s design was highly controversial at the time, it is now revered as one of New York City’s finest buildings.

Wright’s Death

Frank Lloyd Wright passed away on April 9, 1959, at the age 91, six months before the Guggenheim opened its doors. Wright is widely considered the greatest architect of the 20th century, and the greatest American architect of all time. He perfected a distinctly American style of architecture that emphasized simplicity and natural beauty in contrast to the elaborate and ornate architecture that had prevailed in Europe. With seemingly superhuman energy and persistence, Wright designed more than 1,100 buildings during his lifetime, nearly one third of which he designed during his last decade. The historian Robert Twombly wrote of Wright, “His surge of creativity after two decades of frustration was one of the most dramatic resuscitations in American art history, made more impressive by the fact that Wright was seventy years old in 1937.” Wright lives on through the beautiful buildings he designed, as well as through the powerful and enduring idea that guided all of his work—that buildings should serve to honor and enhance the natural beauty surrounding them. “I would like to have a free architecture,” Wright wrote. “Architecture that belonged where you see it standing—and is a grace to the landscape instead of a disgrace.”