William Tunberg initiated into Phi Delta Theta at the University of Idaho and eventually transferred to and graduated from the University of Southern California in 1963.

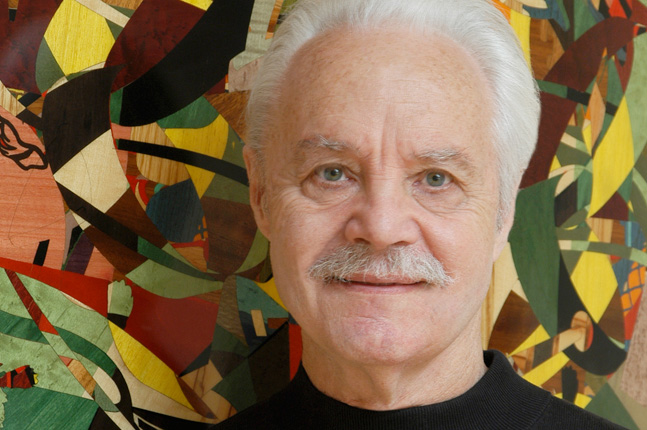

In a recent article in Klassik Magazine, writer Laura Gomez highlights Phi and 83-year-old artist William Tunberg’s art and asks some questions to help us get to know the man and artist and understand his impact on the world through art.

Excerpts

In creating marquetry sculpture, Tunberg calls upon his lifelong love of assemblage and classical drawing. Tunberg‘s materials are exotic natural and dyed veneers that he fragments, assembles, and reassembles, then laminates over complex sculptural forms of his own devising.

Tunberg considers the resulting imagery as personal narratives expressed in his own language and mode of communication.

Tunberg pioneered the use of marquetry in abstract expressionism and fine art sculpture. In doing so, Tunberg created a powerful new art form.

Historically, during the time of Louis XIV, marquetry was the most highly prized of all arts. Marquetry was used as a decorative appliqué to furniture and functional objects. In the early 19th century, marquetry was put aside as a very expensive mode of ornamentation.

Except for its logistical complexities, Tunberg‘s use of this classical technique has little in common with traditional marquetry, as traditional marquetry uses floral designs and natural scenes as decorative motifs. Bypassing traditional applications, Tunberg concentrates on fragmenting imagery and arranging the imagery into surreal combinations and juxtapositions to create a dialog of irrational reality.

Though the process demands precision and focus, and is fraught with difficulty and frustration, the results are worth all the effort. Marquetry is unrivaled for sheer beauty and visual drama.

Q and A

College: University of Southern California. BFA in Architecture (1963); MFA in Sculpture (1965).

Favorite Colors: Black and green (but my favorites are always changing).

How long have you been in art? How did you start? I started as a child copying postage stamps. I’ve never considered being anything else. My loves have always been life drawing and assemblage. In the late-’80s I started using marquetry in my assemblages and it soon became my dominant medium. I think this is because it was extremely difficult to use in fine art sculpture, and it became an overwhelming challenge to bridge the gap between the decorative and fine arts.

How would you define yourself as an artist? Disciplined.

Would you tell us some things about yourself? I was born in Los Angeles and raised in Southern Oregon by my grandparents. My father was a screenwriter in Hollywood and suffered financially during the late-’40s and early-’50s because of the HUAC. I moved 27 times before I finished high school and was shuffled between my parents and grandparents. My grandmother was a religious zealot, but my grandfather was the opposite. He showered me with love and taught me many things — fishing, hunting, construction. He was an ideal father figure. When I graduated from high school, I attended three different colleges, all on scholarships. I obtained a scholarship to USC for my final 1.5 years and obtained my BFA in architecture. The Dean offered me a fellowship for graduate school and I obtained an MFA in sculpture.

After I graduated in the mid-’60s, I established my studio in Venice. As I was becoming an established artist, I worked many different jobs. I worked as a bodyguard for George Hearst during the Herald Examiner newspaper strike, for Ed Kienholz as a studio assistant, for Pierre Adige moving explosives, and as a bouncer. Eventually I became a life drawing instructor at colleges in Oregon and California. By the early-’80s, I was a firmly-established artist in Venice.

Where do you find inspiration? In my wife, Camille.

What are you trying to communicate with your art? I try to convey, in an abstract fashion, cultural dichotomies. For example, I created a sculpture Kanzashi, which uses profiles of Geishas, their hair, and the combs used to keep their hair in place. These combs are beautiful adornments but are also used as self-defense weapons.

What art do you most identify with? For sculpture, I don’t identify with other art. I’ve established a uniqueness in contemporary fine art sculpture by using marquetry as my medium and employing its ancient techniques. I haven’t seen other sculptors using marquetry in this fashion. For drawing, I identify with Ingres.

Why do you do what you do? I don’t know. I was born this way. I’ve never done anything else.

What does “being creative” mean to you? Being creative means being innovative.

Where can readers find your work? At www.williamtunberg.com and at Fabrik Projects, www.fabrikprojects.com.

Which is your most cherished piece? My most cherished piece is the piece I’m working on. Once it’s finished, I set it free. It’s born and then it goes off on its own.

If you had an exclusive collective exhibition with other artists work, who would you choose? Ed Kienholz, Joseph Cornell, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, and Norman Rockwell.

What do you see as the strengths of your pieces, visually or conceptually? Abstracted marquetry images over 3-D forms. Mixing frenetic action with quiet spaces.

What aspect of your work do you pay particular attention to? Diagonal movement.

What Role does the artist have in society? To convey information. Compare Rodin and Kienholz and the way each treats the human form — Rodin glorifies human strength and Kienholz ridicules human values. Their roles are the same: to convey to the viewer different aspects of humanity.

What is your most treasured memory? Marrying my wife.

What for you is the most enjoyable part of your art? The most enjoyable part is seeing the piece completed — seeing my concept come to life.

What famous artists have influenced you, and how? Bouguereau, Ingres and Rockwell because of the way they use space, especially negative space.

What other interests do you have outside of art? My wife and I have a collection of Alfred Shaheen vintage Hawaiian clothing and fabrics. Shaheen‘s fabric designs have had a major influence on the marquetry designs of my furniture.

Prizes: Stanley Jameson Award, USC (1964); First Award, Graphics, All California Art (1965); First Purchase Award, Sculpture, City of Los Angeles (1972); Annual Design Award, Furniture Designer of the Year, Angeles Magazine (1990); Veteran’s Memorial Competition Winner, City of Santa Monica (1991).

You seem to be very aware of the history of works. Where do you see films, photo exhibitions, art performances today? I try to stay away from contemporary art exhibits, as I don’t want to be influenced. However, I love ancient art and visit the Getty Museums in Los Angeles and Malibu frequently. I also read quite a bit.

How would your life change if you were no longer allowed to create art? I can’t imagine. My life would be dreadful.

What do you think about the art community and market? Too much mediocrity.

Should art be funded? Why? No. Art should stand on its own merit.

Which of your projects has given you the most satisfaction? My projects for Chapman University have given me the most satisfaction. I’ve been privileged to create sculptural communion tables, crosses and other religious art for Chapman’s Interfaith Center. I’ve also created vessels to house Chapman’s collection of rare antiquities. For example, I created an Ark for a Holocaust Torah that was smuggled to safety during WWII, and sculptural showcases for ancient Bibles, Books of Mormon and the Islamic Quran.

Who are the writer’s you admire the most? Friedrich Nietzsche and Mark Twain.

What about architects and designers? Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Gottfried Semper.

What else are you working on at the moment? Next projects? I’m currently working on a wall sculpture and a chair. Both pieces are forms I just designed and have never used before.

For a complete list of his past exhibitions and awards and commissions, see his website www.williamtunberg.com.