When Illinois basketball legend Dave Downey married his high school sweetheart in Canton, Ill., he asked a good friend and teammate, Bill Burwell, to be a groomsman.

Burwell, who is from Brooklyn, N.Y., is black. And it was the early 1960s. Downey didn’t think much about it, but the folks in Canton apparently did.

The father of one of the bridesmaids refused to let his daughter walk down the aisle with Burwell. When Downey’s fiance came to tell him the news, he told her to find another bridesmaid.

As it happened, Downey’s future sister-in-law stepped in and said, “I’d be proud to walk down the aisle with Bill.”

Basketball opened doors for Downey, the son of a coal-miner from Alabama, who went on to law school and a successful business career. It also helped him build bridges across cultures and led, indirectly, to his role in the desegregation of Champaign schools in the late 1960s.

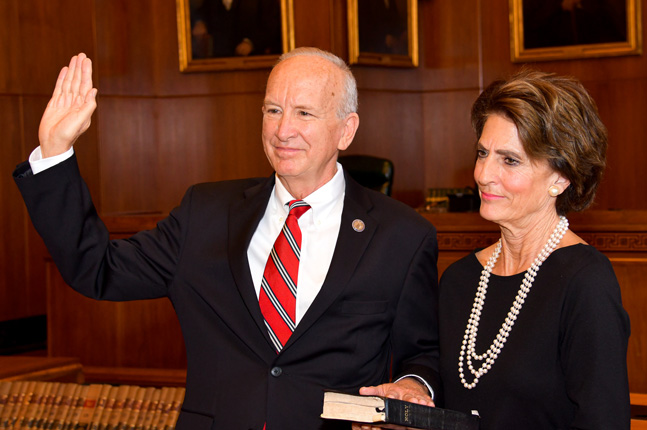

Downey — to be honored at today’s game against Indiana for his $2 million contribution to the State Farm Center renovation — played basketball at Illinois during a period of great racial change.

Manny Jackson and Govoner Vaughn, the UI’s first two African-American players, were seniors when he joined the UI team in fall 1959. Though freshmen couldn’t play at the time, he practiced every day against Vaughn, who “taught me a lot,” Downey said.

Jackson and Vaughn showed “great tolerance and dignity” in the face of intolerance, he said. The team itself had no racial issues but ran into problems off the court, he said.

During one trip to Lexington, Ky., in the early ’60s, Downey and others noticed that the African-American players on the team weren’t being served in the restaurant of their hotel. He asked why and was told, “They’ll have to eat in the kitchen.”

“We got up and walked out,” he said. “If you can’t serve them, you can’t serve us.”

Downey grew up in a rented home in Canton with no indoor plumbing. His mom, Beulah Downey, had a seventh-grade education, and his dad couldn’t read or write. John Downey had been to school one day in his life: he showed up, stammered, was laughed at and said “he’d never go back,” Downey said.

After leaving the UI, Downey went on to law school — talking the dean into letting him in before taking the LSAT — and played on some local amateur basketball teams. One was organized by Wardell Jackson, owner of the Monarch Tavern, who had sponsored athletic teams for black children before they were allowed in Little League, he said.

“I was the only white guy on his team,” Downey said.

It was the mid-’60s, when racial tensions were high across the country. Downey was recruited to serve on a Model Community Coordinating Council organized by former News-Gazette owner Michael Chinigo.

“I was a 20-something, fledgling business guy,” he said, but he also was an athlete known well in the black community. William Smith, manager for Downey’s amateur team (and later a lawyer and administrator at Ohio University), once described him this way: “Dave was black before Bill Clinton was.”

Downey’s business associates warned him that getting involved could hurt his insurance business. Downey dismissed their concerns. They told him the same thing, he said, when he grew a beard in 1975 on a cross-country trip in a motor home with his kids.

The coalition — which included the Urban League, NAACP and local activists — worked to integrate the city fire department and the Ironworkers’ Union, among others.

In 1968, Downey was asked to serve on a committee formed to desegregate Champaign schools.

“There was a lot of tension,” Downey said, from both white and black parents who didn’t want change or busing. But evidence at the time showed that African-American children did better in integrated schools, and white children “did no worse,” he said.

After months of meetings and testimony from experts, the panel recommended creating a magnet school for the arts at Booker T. Washington Elementary School, which was then all-black. The idea was to entice white families to send their children to school in north Champaign. Black students were bused to schools across the district.

Not everyone on the committee agreed on the solution, but they “all wanted what was best for kids,” he said. “We were all able to reach a consensus and convince the community that it was worth a try.”

The school board agreed, though not unanimously.

It was harder on black families, Downey said, as busing made after-school activities difficult for them.

“These are good arguments for neighborhood schools, but you needed to integrate the classroom if you were going to integrate the community,” he said. “It would be better if you had naturally integrated neighborhoods, but there still aren’t many of those.”

Downey, who lived on Armory Street at the time, sent his own children to Washington; it seemed “hypocritical” to do otherwise, he said.

Was the plan a success? No, Downey said, calling it “a work in progress.” He didn’t think the community would still be debating racial issues 50 years later.

“Progress hasn’t been as fast or as deep as I’d hoped,” he said.

While he doesn’t begrudge the educational choices individual parents make for their children, he believes that “being socialized and living in an integrated society is more healthy than not.”

“Free public education is what makes a difference in this community,” he said.